In 1501, 26 year old Michelangelo commenced work on his iconic sculpture David. Michelangelo was ‘considered the greatest living artist in his lifetime’ (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2012) and his art is still accessible and clearly revered more than 500 years later. Like many historical sculptural works David stood tall for over 350 years outdoors before being moved out of the weather, and has remained on public display to millions of visitors in the gallery of the Accademia di Belle Arti Firenze ever since.

In 1991, 26 year old Damien Hirst, today’s most successful living artist, delivered his iconic commission, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, to art collector Charles Saatchi. Unfortunately the shark at the centre of this work deteriorated badly in subsequent years and in 2006 it was replaced by another, more carefully preserved specimen.

The controversy surrounding Hirst’s conceptual art has continued to generate record sales, wide publicity and enormous wealth for the artist and his investors, but the question remains: Will today’s highly priced contemporary art last hundreds of years?

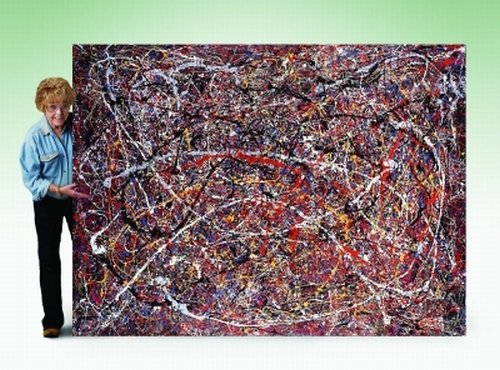

I asked Michael for his thoughts on creating multi-generational art and what steps he takes to craft pieces that endure.

“Conservation of works: I think it is pretty important as an artist to conserve your works as best you can, and prepare them in a way that is sensitive to them lasting a long time. Because if someone’s paying a fair bit of their money for a work of art then they want to know that it’s going to last. It sort of makes common sense. But it does mean that you have to spend a little bit more money on products, on art materials, canvases, linens, paints, good artist-quality stuff so it actually does last longer.

For oil painting you’ve got to learn a lot about layering, how long you have to leave each layer between coats of paint, and fundamental things about the properties and behaviour of different materials in order for your works to last.

The style that I paint is multi-layered, which can be prone to cracking and other problems, so I get good quality linen, give it a solid base and good priming. And when I do my layering I give them ample time to dry, at least a week between each working depending on the thickness of the paint. I sometimes use mediums as well which make drying a bit more consistent, because different paints have different drying times.

Also you don’t want your colours to fade but if you get artist’s quality paint pigments they won’t do that. I think the quality of paint these days is a lot better than it used to be. You’d imagine that it’s improved over time… I’m not positive about that but you hope it would have if you use good quality ones.

It doesn’t matter how good your materials are you can still make a bad painting out of it. Sometimes a painting just doesn’t turn out as well as you’d hoped. There’s nothing you can do about that except start again. In general you’ve just got to do the best you can, be as professional as you can, and if people are going to spend money on your work, aim to give them a good product.

I think if your works turn out to be really beautiful, insightful works and they are collected, what you want in a couple of hundred years is colours that remain the same and paint that doesn’t peel or crack off. Your art might not ever get to that stage in acknowledgement, but as an artist if you give yourself respect and make it your life’s work you may as well spend the time preparing your works well.”

References:

1. Michelangelo 2012. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 16 April, 2012, from <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/379957/Michelangelo/>.

2. O’Hagan, S, 2012. Basically, it’s just a big aquarium with a dead fish in it, The Weekend Australian Magazine, April 14-15, pp 20.

Conservation of contemporary art is a new problem for museums and collectors. Check this out if you are interested in any further reading.

From Sharks to Sugar: Addressing Conservation Issues of Non-Traditional Contemporary Art Media. Masters thesis by Jennifer Levy as part of the Museum Studies program at John F. Kennedy University in Berkeley California, 2008.

Related posts:

Keep all your art receipts: the importance of provenance.