Check your pockets. Phone/camera/video?

Nearly everyone on the planet has access to some form of photographic device, and images from our lives are shared everywhere.

While the quality of reproduction steadily climbs the part that photographs struggle to convey are the emotions of the photographer. How were they feeling when they pressed the button? What inspired them to take that image and why should anyone else care about it?

How many times have you seen photos from a friend’s dream holiday that mean nothing without their excited narration?

Video and audio bring us closer to a shared experience but we still feel the disconnection of viewing rather than participating.

How figurative painting can bridge the disconnection

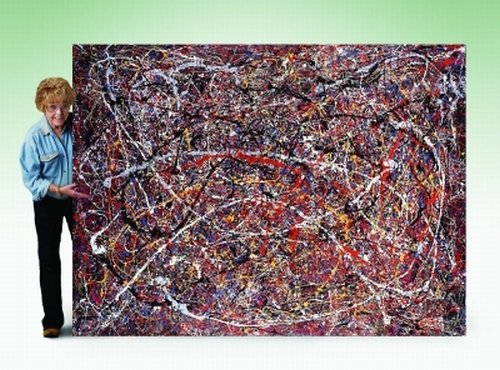

For an artist like Mike, emotion is the core of his practise. If a scene does not move or touch him in some way he has no interest in capturing it. Oil painting can take a long time and involves going over and over the canvas to build texture, intensify colour, and experiment with ways to communicate his thoughts. Without some sort of emotional connection to a painting there is no incentive to keep reworking it; and without the drive to convey emotion a painting can emerge lifeless and flat.

The advantage figurative painting has over photography is its imperfection. When a scene is rendered in paint we see something that is different to what our eye normally sees. Strange colours, rougher textures and visible brush strokes shock our subconscious into looking more closely. Our minds need to work harder to recognise reality and so we automatically spend more time assessing our response.

Do we agree or disagree with the artist’s interpretation? Why did he paint it like that? Do we like it?

If the painting draws us in, we want to understand more about why and how the artist painted it. Understanding his motivations helps us ‘read’ the painting. And so, we participate. We respond.

Art and social commentary

Mike has participated in a number of art workshops for people in aged or assisted care (with and without mental illness) and is always fascinated by the characters he meets. Sadly, listening and chatting to residents often reveals cracks in family relationships; few visitors; and in many cases a reliance on television to replace normal social interaction. The Common Room at Royal Avenue is his response to a situation he found distressing. Rather than interacting with loved ones, or each other, residents were slumped in boredom, staring blankly at midday television.

Stages of this work showed much more detail in the faces (see below) but in the end Mike felt the work needed more rawness to convey his impression of societal breakdown and despair. This may not be a pretty image, but an artist’s instinctive desire to record his emotions in figurative work may show future generations a snapshot of the 2000s that is not recorded photographically.

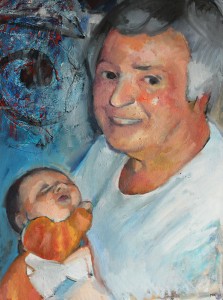

Art and memory

This memorial commission was painted entirely from photographs but Mike’s emotional involvement was still required.

Mike had never met Gillian but conversations with her family described the strong bond between her and her grandson. Several photographs were supplied, including Eric at different ages, but Mike chose the image he felt best represented Gillian. He acknowledged Eric as an older child with the swirling graphic: the symbol from a t-shirt his grandmother wore that the toddler particularly liked.

Mike’s empathy as a son and a parent helped him illustrate the small stories that bind a family together. Photos and videos are filed away for occasional viewing but everyone who comments on that painting will participate in its narrative. The explanation behind the work is simple, but the telling of it is a loving reminder of a grandparent lost too soon.

Art and conversation

With endless technology at our fingertips you’d expect the audience at art museums to drop. Instead, art institutions are reaching out to the people and it’s working. They are broadening their programs to include all ages; making events more social; curating a wider range of shows; increasing educational content and using technology to engage audiences and share art more widely.

Here in Melbourne huge crowds have turned out for the last eight years to see figurative art through the ages in the NGV Winter Masterpieces series. Australians also embrace contemporary portraiture with healthy attendance figures for the Archibald Prize and related competitions. Clearly we haven’t lost our appreciation for oil on canvas as a form of entertainment.

Art and history

History has always been recorded by artists. From cave painting to modern art, the value of artists is a gift for observation combined with a desire to share. Writers, painters and musicians all strive to communicate in their own language and their work broadens us all.

“The arts link society to its past, a people to its inherited store of ideas, images and words; yet the arts challenge those links in order to find ways of exploring new paths and ventures.” – John Tusa, The Guardian, 13 Dec 2005.

“The arts are not just a nice thing to have or to do if there is free time or if one can afford it. Rather, paintings and poetry, music and fashion, design and dialogue, they all define who we are as a people and provide an account of our history for the next generation.” – Michelle Obama, 18 May 2009.